Ihsanullah Tipu Mehsud

March 09, 2026

Pakistani Taliban's gradual shift in recent years from a jihadist movement — which transcends ethnic affiliations — to an ethnically driven militancy is ultimately undermining its broad influence and appeal.

This new idealogical orientation of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and few other separate factions of Pakistani Taliban has effectively limited its appeal and influence to a specific region, potentially reducing its broader ideological impact and reach among other ethnicities. This development will certainly benefit Pakistani government by containing the group's recruitment drive, at least in Punjab.

In recent interactions, a few non-Pashtun individuals, who sympathize with the Pakistani Taliban-led jihad, asserted that the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and other factions of the Pakistani Taliban are increasingly turning into traditional tribal jihadist militias, similar to the Mujahideen groups that fought against the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan in the ’80s.

"During the American invasion of Afghanistan, people from various ethnic backgrounds united to participate in the Taliban-led jihad," one individual who declined to be named said during the interview. "However, it now appears that this unity is fracturing, transforming into an ethnically driven conflict that is losing its adherence to the actual essence of jihad. This shift is not limited to the Pakistani Taliban; the Afghan Taliban also exhibit similar attitudes, with their social media accounts frequently using abusive language against non-Pashtun ethnicities."

This trend is increasingly alienating like-minded jihadists, primarily from Punjab and Urdu-speaking areas of Karachi, who previously constituted a core operational, ideological and propaganda base for the Pakistani Taliban.

Another interesting development was the issuance of divergent statements by two prominent regional jihadist organizations amid escalating Pakistan-India tensions following the Pahalgam attack.

On May 7, hours after India struck Pakistan, Al-Qaeda's regional branch, Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS), released a statement strongly condemning India for its attacks on Pakistan and stating that jihad against India is obligatory for Muslims in both India and Pakistan. In stark contrast, the next day the TTP issued its own statement on Indian attacks and harshly criticized Pakistan, without uttering a single word of condemnation or criticism against India in the entire statement.

While in the past the TTP used to threaten India whenever the tensions between the two countries arose, such deviations from its past stance may further diminish TTP's influence in mainland Pakistan and will strengthen the Pakistani state's narrative that TTP is an Indian proxy against Pakistan.

The significance of this development has been already witnessed when carefully monitoring narratives shared by militants across the jihadist spectrum. Interestingly, several prominent voices from Afghan Taliban as well as Pakistani Taliban linked social media accounts have harshly criticised Pakistan, fostering a narrative according to which Pakistan—and Pakistan’s military and politicians—is not behaving as a truly Islamic country, stating that the fight between Pakistan and India is not jihad but a clash between two Western-modelled countries, and there is no difference between India and Pakistan. Crucially, the same propaganda has been long framed by other jihadist organizations—primarily the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP)—against the Afghan Taliban and the TTP. For instance, the ISKP repeatedly stated that the Afghan Taliban are a proxy of the Western world, China, and Russia in their fight against the Islamic State, and even described them as “murtad” (an apostate, referring to someone who abandons their Islamic faith). Similarly, the ISKP argued that both the Afghan Taliban and the TTP are merely nationalist ethnic movements rather than genuine Sharia-abiding jihadists. The result is an overlapping of narratives among jihadist militants who attempt to outbid each other and attract more recruits with their narratives.

While social media accounts affiliated with the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban vehemently criticized the Pakistani state, blurring the distinction between the government and its Muslim citizens. On the other hand, a number of Western Islamist scholars expressed their vocal support for Pakistan, emphasizing its Muslim-majority status and arguing that Islamic principles transcend national borders.

This infusion of these growing ethnic, nationalist and Pakistan-centric attributes into jihadist ideology by the TTP appears to be a tactic borrowed from Baloch armed separatist groups. These organizations primarily exploit grievances like poor governance, unequal resource distribution and lack of genuine political representation in Balochistan, indoctrinating the new generation of Baloch with so-called dreams of a separate and independent state. As a result, in recent years, the narrative-building efforts against the Pakistani state by Baloch armed separatists have been somewhat successful in fostering growing alienation among Baloch youth, particularly the educated segment, who subsequently take up arms against the state. Notably, a significant proportion of suicide attacks carried out by Baloch militant groups have been perpetrated by educated young individuals, even females.

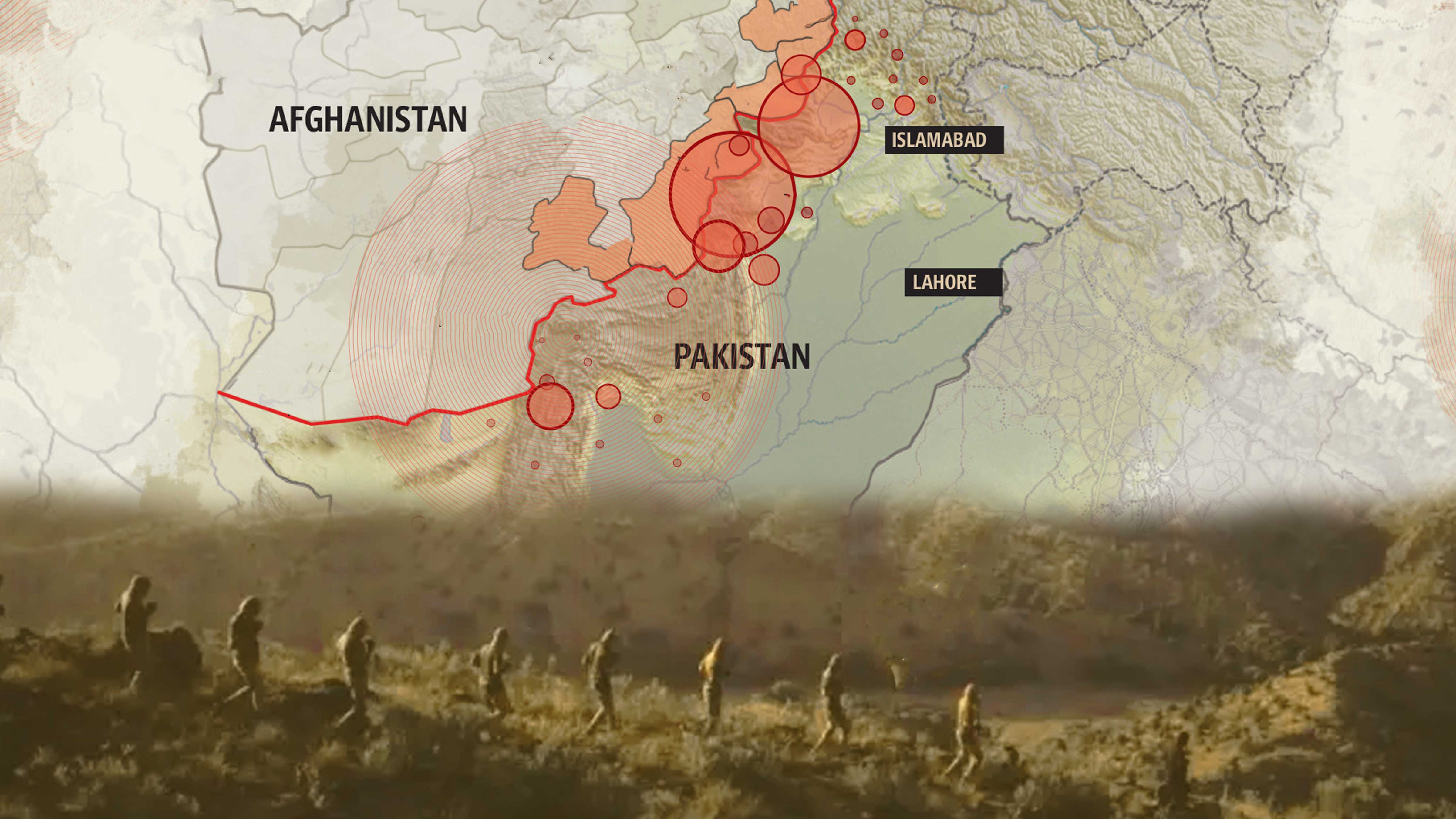

Similarly, Pakistan's over-reliance on force to combat militancy, while ignoring legitimate local grievances, has allowed jihadist narratives to gain traction in certain Khyber Pakhtunkhwa communities, particularly in former tribal areas. This trend is evident in the growing social media praise for Pakistani Taliban attacks on security forces. If this approach continues, it may prompt some local youth to tacitly support the Pakistani Taliban against the state, even if it does not spark an organized ethnic militancy similar to that in Balochistan.

Furthermore, the environment is complicated by the issue that Pakistan's counter-terrorism approach is predominantly based on a reactive rather than proactive attitude. The authorities often allow local issues, frequently at the level of a tehsil (local administrative unit) or district, to escalate and intensify before responding. In time, the issue ultimately becomes more complex and significantly more challenging to manage effectively. As a result, these issues frequently reach a scale that affects the entire province.

In contrast, militants—both jihadists and ethnic/separatists—appear to be more proactive, adeptly exploiting local grievances and capitalizing on existing discontent to further their specific objectives and agendas.

The surge in militant activities, particularly in Balochistan, suggests that Pakistan's extensive counter-terrorism efforts have been undermined by neglecting governance issues, impeding progress against the militant threat. As a result, militant groups continue to flourish, driven by their anti-state narrative-building efforts that fuel sustained recruitment and revenue generation.

In the wake of the ideological transformation, the Pakistani Taliban's operational dynamics have also undergone a significant shift. Unlike in the past when civilians bore the major brunt of attacks, the TTP-led assaults resulting in civilian casualties have drastically declined. In areas where the TTP maintains a concentration, locals are becoming increasingly indifferent to their presence.

When interacting with a few locals who claimed to have seen a frequent presence of TTP militants in their respective areas, they stated that they do not feel threatened by the presence of militants as the latter avoid disturbing or harassing them. "They come and then disappear. This time, they are not bothering us. They even release captives who are government servants and locals upon our requests. This was not the case previously. They killed hundreds of local elders over minor suspicions in the past. But now, we don't feel threatened the way we used to in the past. We just want to live in peace," said a local elder from District Tank in Southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, who requested anonymity due to security concerns.

The current TTP chief, Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, reportedly maintains discipline within the TTP and ensures internal accountability when groups or individuals violate the militant group's set guidelines. On several occasions, key commanders deemed to have breached the group's guidelines have been removed or sidelined and later reintegrated after assuring that such incidents would not recur.

Furthermore, as per their operational guidelines, the TTP leadership has increasingly discouraged frequent large-scale attacks, aiming to avoid civilian casualties, minimize manpower losses and prevent pressure from the Pakistani government on its main backer, the Afghan Taliban.

One local dynamic that might shed light on the complexity of the security scenario is a trend recently observed in Lakki Marwat district, in southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Here, local communities opted for the formation of peace committees to contain Taliban attacks. As per locals, the development is organic and largely driven by the militants' abductions, killings and house demolitions of police personnel and other government employees, hailing from the local communities. Government jobs are considered a vital financial lifeline for the district.

The scenario is further complicated by the emergence of a concerning trend in Pakistan's fight against militancy. On one hand, non-state actors have developed new political strategies that have led to the formation of unexpected alliances, particularly with Baloch armed separatists, putting aside ideological and tribal differences. On the other hand, at the state level, Pakistan is grappling with intense political and social polarization.

This divide undermines the country's ability to present a united front against terrorism and provides ample opportunity for myriad militant groups to exploit these fault lines. As a result, unlike past large-scale military offensives against the Pakistani Taliban, which garnered broad support from political parties and local communities, the current landscape is marked by extreme division, often resulting in the postponement or termination of counter-terrorism operations in certain areas and on certain occasions.

Another alarming trend for the Pakistani government is the growing number of Afghan Taliban fighters joining the Pakistani Taliban's ranks for attacks inside Pakistan, in addition to the Pakistani Taliban leadership's presence in Afghanistan. Despite the interim Afghan government's persistent denials, the use of Afghan soil for attacks in Pakistan and Afghan militants joining the TTP are undeniable facts.

In order to counter this, Pakistan's authorities also need to enhance internal security measures, including effective border control, pre-empting large-scale attacks through advanced communication tracking and tracing militant movements through extensive ground intelligence. In recent months, it appears that Pakistani intelligence has made some significant inroads into the ranks and files of both the Pakistani and Afghan Taliban. The systematic elimination of entire tashkeels (fighting units) of Pakistani Taliban in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border areas—as they attempt to infiltrate into Pakistan—by the hands of Pakistan’s security forces strongly suggests that Pakistani Taliba’s movements have been largely compromised recently.

Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, the leader of the Pakistani Taliban (TTP), has released two statements, one audio and one video, in recent days, emphasizing the group’s ideological and operational aspects.

In the first audio statement, released through the group's propaganda mouthpiece Umar Media, he criticizes Pakistan for its past alliance with the US, particularly in toppling the Taliban-led Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan post-9/11.

Mehsud urged prominent religious scholars, including Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman (Jamiat Ulema Islam chief), Mufti Taqi Usmani (Pakistan’s grand Mufti) and Maulana Tayyab Tahiri (leader of Panjpiri school of thought) to provide Sharia-based arguments proving the TTP's armed struggle is against Islamic law. If they succeed, the TTP will abandon its struggle and seek forgiveness for past actions. However, if they cannot, Mehsud demands they refrain from siding with the government by labelling the TTP as "Fitna al-Khawarij" and instead remain silent.

These remarks appear to seek ideological support from Pakistani religious scholars for the TTP's armed struggle. Senior scholars, in recent years have questioned the group's jihad justification since the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Mehsud argues that the US continues to significantly influence Pakistani government policies, and the withdrawal doesn't imply Pakistan has severed ties with the US alliance.

In a significant ideological blow in recent years, Pakistan's influential religious scholars, who share the same school of thought as the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) have publicly declared the TTP's armed struggle in Pakistan as contrary to Sharia principles and illegitimate.

The TTP's core ideological strength in the early 2000s, even before the group's formation, stemmed from a decree by around 500 religious scholars who legitimized their fight against Pakistani security forces as jihad. This was largely due to Pakistan's participation in the US-led War on Terror against Afghan Taliban and Al-Qaeda.

TTP leader Noor Wali Mehsud, himself a religious scholar, has consistently urged Pakistani scholars to support the TTP on ideological grounds. However, his efforts have been unsuccessful so far.

On the other hand, Pakistani religious scholars find themselves caught between the Pakistani state and the TTP, with both sides seeking their support and ideological legitimacy in their fight against each other.

In his second statement, a video one, Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud emphasized operational security, cautioning TTP fighters to exercise extreme caution with the use of cell phones and movements to avoid detection by Pakistani security forces. He warns against carelessness that could compromise their operations and allow security forces to gain the upper hand.

In the same video statement, Mehsud has also urged Afghan Taliban fighters not to join TTP ranks to fight in Pakistan, claiming TTP has sufficient manpower. Instead, he asked them for support in the form of finances, advocacy ("tongue") and media efforts ("pen"), while emphasizing the obligation for Afghan fighters to obey the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan's directives in this regard.

In the video statement he also justifies Afghan interim government efforts to engage “non-Muslims” governments for the betterment and strengthening of Islamic Emirate.

After an almost complete diplomatic breakdown between Afghanistan and Pakistan over the issue of Pakistani Taliban attacks on Pakistani soil, Islamabad re-engages in diplomatic efforts with the Taliban-led Afghan interim government. One notable progress, which few diplomatic sources attribute to the ongoing diplomatic efforts, is a reduction in mid- or large-scale attacks by the Pakistani Taliban factions and a decrease in casualties among security personnel over the past few weeks. While the announcement of the TTP's "Al-Khandaq" spring offensive had previously raised concerns about potential major attacks in Pakistan, particularly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, no large-scale attack has occurred (except one attack by the Pakistani Taliban on May 9 which killed at least 9 security forces personnel in Shakai Valley, South Waziristan Lower).

There is also one theory circulating these days that there might be a tacit understanding across the border—where the Pakistani government has been asked to refrain from taking kinetic action against the Pakistani Taliban across the border in Afghanistan, instead keep engaging and targeting them when they attempt to infiltrate into Pakistan.

Regardless of the veracity of the claims, however, expectations of sudden changes and instant outcomes from the process are unrealistic, given the range of complexities involved. It is a process that requires patience and time.

However, there remains the potential risk that a single large-scale attack staged by the Pakistani Taliban might derail the entire process and push Pakistan and Afghanistan toward an armed confrontation.

The Taliban, both Pakistani and Afghan, criticize Pakistan for its decision to join the US-led War on Terror and assist Western forces in toppling the Taliban's first regime post-9/11. Ironically, they completely overlook the Pakistan state's substantial clandestine support to the Afghan Taliban against the Americans and the two Afghan governments of Karzai and Ghani. There have been multiple instances where Pakistani intelligence has rescued top Taliban leaders, who are currently holding ministerial positions in the current Afghan government, from US counterterrorism operations, particularly drone strikes. This was done by alerting them that the Americans had located them and were about to launch an attack, prompting them to evacuate the area immediately.

For years, Pakistan has not only provided protection and refuge to the operational leadership of the Taliban but also allowed their senior ideologues to operate freely in the country, running a network of seminaries in various parts of Pakistan.

Last year, a senior US official, highlighted the complexities of this relationship during a meeting, remarking that it would have been much beneficial for Pakistan if it had not supported the Taliban and instead stood with the US against them.

“Pakistan might not have faced the current wave of Pakistani Taliban-led militancy if it had taken a different position that time,” he commented.